Love for the World

The church has no hymns about asphalt or skyscrapers, no paeans to internal combustion engines, no alleluias for shopping centers. Instead, great psalms and anthems express awe of the natural world.

“The grasslands of the wilderness overflow; the hills are clothed with gladness. The meadows are covered with flocks and the valleys are mantled with grain; they shout for joy and sing.”—Psalm 65:12-13.

Or: “For the beauty of the hour, of the day and of the night, hill and vale and tree and flower, sun and moon and stars of light—Lord of all to thee we raise this our joyful hymn of praise.”

After all, according to Scripture, the world began with a garden.

For Bonnie Lamberth, a member of the Cathedral of St. Philip, worship during COVID-19 isolation had an upside she didn’t expect. On Sabbath days when the weather was good, the priests conducted Sunday services outside. As she watched the livestreams, she found “that worship with nature, with the outdoors, as background has been so rich and so intimate. I think the climax was on Easter Sunday with the celebration of the Eucharist outdoors, surrounded by dogwoods and azaleas in bloom. I felt a kind of joy-filled realization of being surrounded by the presence of God beyond what being inside is like.”

Lamberth discovered in her seclusion what many people seek, according to Robert Gottfried. “Today many Westerners seem to yearn for a return to the Garden, a place where humans and the natural world relate intimately to one another,” he wrote in Economics, Ecology, and the Roots of Western Faith. Gottfried directs the Center for Religion and the Environment on the thirteen-thousand-acre “domain” of the University of the South (Sewanee). His goal, and that of the center, is to help the church reconnect with the garden and to help Christians become master gardeners of sorts. One way of doing that is through a curriculum called Living in an Icon, for individuals or small groups. “Because all life comes from God, Living in an Icon does not create separations between the natural and the human or the body and the spirit,” the introduction says. “By growing spiritually in a manner that includes all creation, human and nonhuman, we heal the false divisions we have created between us and the rest of creation.”

The Confluence Trail winds through the trees.

A birdhouse installed along the trail years ago still offers shelter all year.

A signature South Fork Trailhead marker helps guide the way.

Everything we do—the way we work, the way we shop, the way we eat, the way we spend our leisure time—has an impact on the planet, Gottfried said in a recent interview. Connection to nature, connection to humankind, and connection to God are all related. And much of what humans have done for the last few decades has taken a big toll on the relationships.

Just as we show compassion for our fellow human beings who are hurting, we need to show compassion for Mother Earth. And true compassion—kinship, partnership—means not only expressing our sorrow for the wrongs or hurts but also trying to alleviate the pain.

Poet and essayist Wendell Berry says that to be faithful, we must care about creation. “The ecological teaching of the Bible is simply inescapable,” he writes. “God made the world because He wanted it made. He thinks the world is good, and He loves it. It is His world; He has never relinquished title to it. And He has never revoked the conditions, bearing on His gift to us of the use of it, that oblige us to take excellent care of it. If God loves the world, then how might any person of faith be excused for not loving it or justified in destroying it?”

But we humans have done a good job of neglect and abuse.

The big picture is pretty frightening—melting polar ice caps, increased intensity of storms, spreading deserts. But the damage is obvious on smaller scales closer to home.

Peachtree Creek is an example. Long before Atlanta, or even Marthasville or Terminus, the Muscogee tribe settled in the area along the creek that, with its tributaries, runs through much of Fulton and DeKalb counties. In those days the pristine stream provided water for drinking and cooking, a home for wildlife, and a means of transportation. When naturalist William Bartram made his trek through the South in the 1700s, he described the water as “clear, cool, and salubrious.”

By 1990, when Dave Kaufman began exploring the creek, it would have been unrecognizable to those early natives who depended on it, or to Bartram.

For thirteen years, Kaufman paddled the creek and researched it. “I found a waterway that lay at the origin of Atlanta’s settlement but had long since been abandoned to become a sewer and a dumping ground,” he wrote in his book, Peachtree Creek. “I came to understand how technology and economics shape the land, how social interaction and political agendas can determine which waterways are fit to drink or, today, not even fit to touch.”

On its way to becoming the capital city of the South, Atlanta built roads, buildings, and parking lots, which increased hard surfaces, which, in turn, prevented rainwater from soaking into the earth. As it flowed into the city’s streams, the excess was more than they could handle, and they overflowed. More people meant more runoff, and the clear, clean waterways became polluted with human and chemical wastes.

Along with the creek itself, its banks and surroundings were abandoned except for use as a depository for trash of all kinds. Then along came the South Fork Conservancy.

Restoration and Development || The organization was founded in 2008 by volunteers who had worked with a larger group to restore the string of small parks designed by Frederick Law Olmstead along Ponce de Leon. They discovered that bringing the parks back to health did more than beautify the land along the street. Neighbors started coming out of their houses and apartments to enjoy the green spaces, and some got to know one another as friends; children ran freely; dogs rolled in the grass. The restorers realized that “for the ability to create and maintain community, there’s a necessity of connection to nature,” said Billy Hall, one of four conservancy founders. “Having human systems interact organically with natural systems was necessary for a sense of health.”

Feeling good about their work and wanting it to continue, Hall and the others looked around for a new project and settled on Peachtree Creek. Their vision was to protect the habitat and connect a series of nature trails along the south fork of the creek and eventually to link all thirty-one miles.

Scores of volunteers joined their effort. Some were grounded in a particular denomination; others found their connection with the divine through nature itself.

“There were dozens of pearls along the south fork of Peachtree Creek,” said Hall, an environmental engineer, “but people weren’t interacting with the creek. There were neighborhoods back to back but no connectivity. The south fork was a wilderness gem, but you couldn’t even get to the creek in most places. If people even realized it was there, they viewed it pretty much as an open sewer.”

Trail map shows current and future south fork and connecting trails.

A first major effort of the conservancy was a toxic thirteen-acre plot contaminated by asbestos and overgrown with kudzu and other invasive plants. In 2010, the conservancy undertook the project. Three years of dealing with DeKalb County government, state, and federal environmental agencies and a U.S. bankruptcy court, along with $2 million in funding, finally resulted in success. Just as a body sometimes needs surgery to remove bad tissue before it can heal, the land had to be cleaned before it could be restored. That required hauling away twenty-six tons of contaminated soil and replacing it with fresh dirt.

Working with volunteers and nearby businesses, the conservancy graded the site into a sloping meadow with a pond that filters rainwater before it flows into the creek. A mile and a half of gravel trails provide a chance to see close up old growth forests, a wetland garden, and clean, flowing water. Visitors may glimpse the pair of great blue herons that call the area home.

The once-toxic area now bears the somewhat ironic name of Zonolite Park, after insulation once made in a factory there.

The big dig: heavy equipment makes space for the bridge that will blend into the landscape where the north and south forks of Peachtree Creek join.

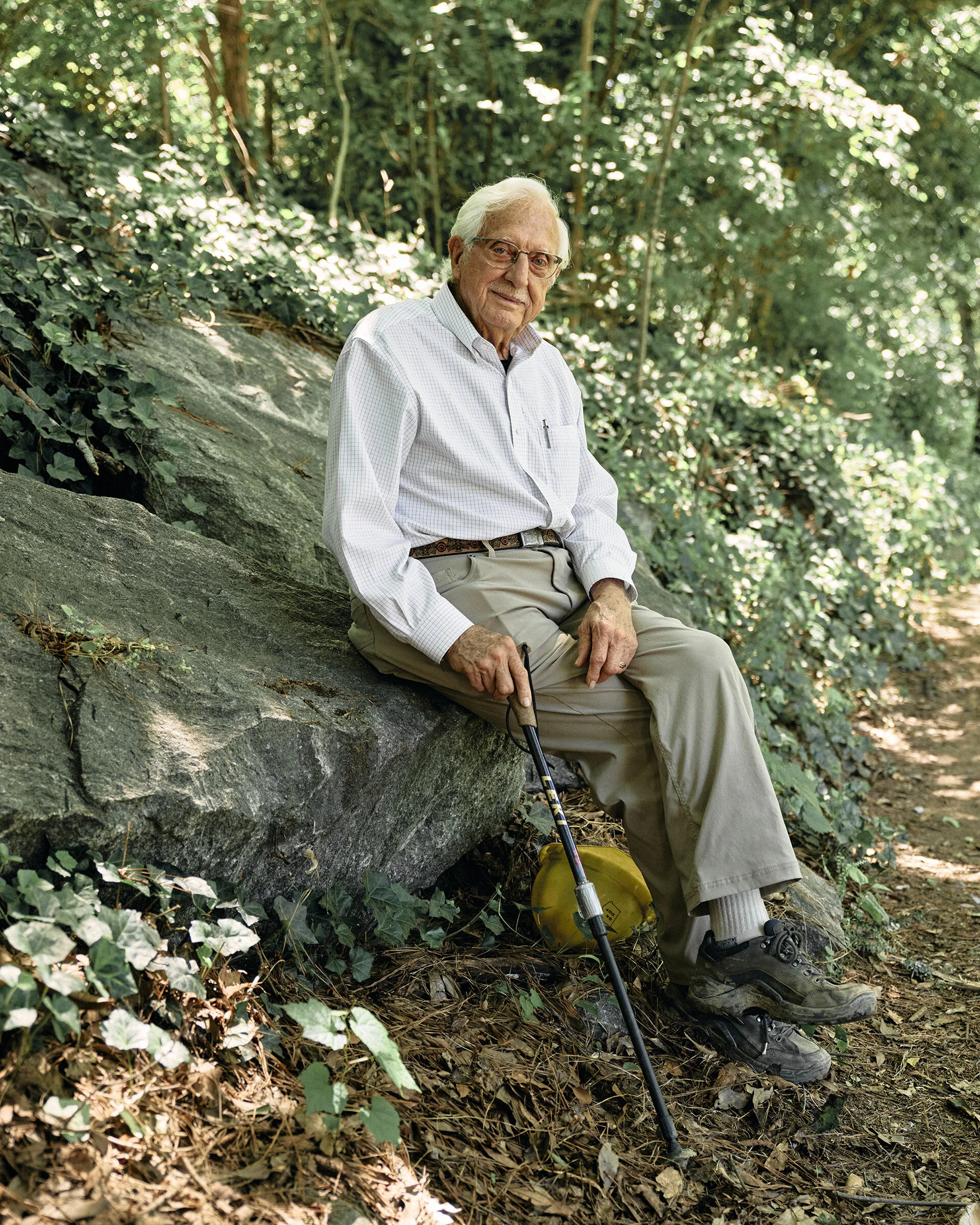

The conservancy has raised more than $6.5 million, recruited more than two thousand volunteers, and completed five miles of trails. The most recent major project is a $2.5 million pedestrian bridge installed in August to connect two trails at I-85 and Georgia 400. When a few smaller projects are implemented, people will be able to walk from the Cheshire Bridge area to the Emory University campus. But the point is not to get from Point A to Point B. “Our vision, simply put, was to create a pathway one could just enjoy, not getting somewhere,” said Bob Kerr, one of the conservancy founders. Walking the trails, he said, he has seen deer, fox, otters, beaver, hawks, ducks. “I feel like it’s an opportunity for so many people who don’t have access to natural systems to see those systems, not only to look at them but to appreciate them. You almost have to see something to learn to love it. If you understand it, you love it even more.”

At eighty-seven, Kerr said, he doesn’t expect to live to see the completion of all thirty-one miles. “I feel like we, as an organization, are leaving something of a legacy,” he said. “I have a tremendous appreciation for the miracle I’m looking at. Regrowth, regeneration, rebirth.”

Fellow conservancy founder Hall puts it this way: “Connecting with nature says we are connecting with a distant past we cannot see, into a distant future we cannot see.”

Bringing Back Butterflies || Art teacher Kristyn Lopez connects directly to the future through working with pupils at DeKalb County’s Henderson Mill Elementary School. She and science teacher Amy Sapp are part of a South Fork Conservancy effort to establish habitats for monarch butterflies.

The bright orange-and-black wings of the monarch make it one of the most recognizable of its species on earth. But eastern monarchs, the kind that migrate through Georgia, have declined by about 80 percent, according to National Geographic. At Henderson Mill, the first school in the state to be certified STEAM—science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics—Lopez and Sapp work together so that their students will see how disciplines interconnect through project-based learning.

Their kindergarteners identified a problem—destruction of the butterflies’ habitat—and looked at possible solutions: What if we plant milkweed? Outside the school was a patch of ground that had been allowed to become overgrown. The children started their project by planting tiny milkweed seeds in small pots of dirt inside, then transplanted them to the now-cleared spot in the schoolyard. As an art project, they made paper monarchs and put them in the hallways of the school.

Flowering Dogwood tree

Monarch butterfly sunning itself

Many of the children came from nearby apartment complexes, “so many of them don’t have gardens at home,” Lopez said. “Some don’t have access to green space at all.”

More than half the school’s students are Hispanic. Many have family in Mexico, some have visited there, and some were born in that country. Those children feel a special connection with the butterflies as they learn about the monarchs’ migration pattern from the Great Plains of Canada southward to Mexico.

In higher grades, Henderson Mill students begin to understand more of the complexity and interconnectedness of the world, such as what happens when a single species disappears, Lopez said.

By fifth grade, they are making observations about care of the earth and how that connects to care of people. Erosion can cause mudslides that destroy homes. Hunger and poverty are related to distribution of resources, which is related to agricultural and marketing practices, wages, and employment.

Beginning with the milkweed seed, the students start to see that what they do will have an impact, for good or bad. Students “start to tell me that paying attention to these things is important because it helps their community,” Lopez said.

If faith as tiny as a mustard seed can move mountains, perhaps a kindergartener’s awareness of the size of a milkweed seed can shape the future.

The Faith Perspective || “Love all Creation, the whole of it and every grain of sand. Love every leaf, every ray of God’s light; love the animals, love the plants, love everything. If you love everything, you will perceive the divine mystery in things, and once you have perceived it, you will begin to comprehend it ceaselessly, more and more every day, and you will at last come to love the whole world with an abiding universal love.”—Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Stephen Ellingson, associate professor of sociology at Hamilton College, describes “three broad ethics of creation care” in his history of the religious environmental movement:

Stewardship, coming out of Genesis 2, is based on an image of God as the sacred creator of “all the material world.” Ellingson says this approach views all of life as sacred and establishes that no one should destroy God’s creation. Environmental problems are seen as rooted in sin or alienation from God and result from disobedience, arrogance, and greed.

Eco-justice, he says, extends the biblical mandate to care for the poor, the weak, and the powerless to the environment.

Creation spirituality, the third ethic, he writes, “attempts to reorient people to understand the proper place of humanity as part of a panentheistic creation” not separate from from the rest of the natural world.

Bob Kerr takes a seat on boulders along the Confluence Trail. “I have tremendous appreciation for the miracle I’m looking at,” says Kerr.

The Rev. Kate Mosley sums up her approach to environmentalism succinctly: “If you care about people, you care about the planet.”

A minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA), until August she was the executive director of Georgia Interfaith Power and Light (GIPL), founded in 2003 by the Rev. Woody Bartlett, an Episcopal priest. The original goal of the organization was to help curb climate change by “greening” houses of worship in Georgia, Mosley said. Today its mission has broadened—to engage “communities of faith in stewardship of Creation as a direct expression of our faithfulness and as a religious response to global climate change.”

A sense remains, however, that compassion for creation should begin at home—in the hallways and sanctuaries of churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples. A study of religious congregations by state showed Georgia with more than 12,000 as of 2012; the Hartford Institute for Religion Research estimated 350,000 in the United States.

“That’s a lot of real estate, a lot of campuses with environmental impact,” Mosley said. “It’s also a lot of religious influence. We know that in the Southeast, religion plays a role in the public square. That’s a lot of influence in terms of cultural value.”

Energy consumption involves many issues, she said. “Coal and its extraction is having a tremendous environmental impact. The ways in which we extract our energy resources, burn them, and waste them is harmful to God’s good earth.”

GIPL received money from the Kendeda Foundation, which supports sustainability, to help religious congregations improve their energy use. Energy efficiency is a double blessing, Mosley said. The less spent on heating and air, the more money is available to help the needy. But spending money on improving energy lacks excitement. “It’s like us with our homes. Who wants to spend money on insulation when you can repaint the living room?” she said.

While looking at what we do in our churches and our homes, we must be aware of the global picture, she said. “This involves a lot more than changing out lightbulbs. We aren’t going to recycle our way out of this mess.”

As an interfaith organization, GIPL has board members from several faiths, each of which has a theological basis for practicing compassion for creation.

Shan Arora, a lawyer and GIPL board member who was born in India, applies two Hindu principles to creation. Dharma, or duty, is one. “What is your duty? To provide for your family. How can you provide for your family if the planet is being destroyed? I have to do what I can to protect the planet.” The second value is ahimsa, or the idea that one should avoid harming any living thing.

Many Muslim environmentalists cite the directive in the Quran that says, “Do not commit abuse on the Earth, spreading corruption.” Islamic environmentalists, scholars, faith leaders, and politicians from twenty countries met in Istanbul five years ago, where they adopted the Islamic Declaration on Global Climate Change to encourage individual Muslims, as well as mosques and Islamic schools, to act to curb environmental abuse.

“‘Do not destroy’ is an ethical principle in Jewish law,” said GIPL board member Rabbi Lydia Medvwin of the Temple. “It’s rooted in the laws in Deuteronomy that forbid cutting down fruit trees in wartime. It’s expanded to include all sorts of ethics—not committing wasteful destruction, kindness to animals. In Jewish law, when we are commanded to rest, even our animals are supposed to rest. There’s a connection between the well-being of the land and our own well-being. The consequence of not tending to earth over time means our own destruction.”

In Judaism the term “tikkun olam” means “to repair the world.” “This is one of those issues so widespread in its impact that it has to be something we all share together,” Medwin said. “The problem was created by all of us together. The solution has to come from all of us together.”

Creation and Justice || Richard and Dorothy Sussman, who live off Lindbergh in Atlanta, regularly walk along the south fork of Peachtree Creek, not just to exercise but also to restore the trail by mowing it, removing invasives, and picking up trash. Both Sussmans appreciate their connection to the natural world and feel an obligation to protect the land. Richard, who spent years working for the U.S. Park Service, is a master gardener who volunteers with Trees Atlanta and Habitat for Humanity. Dorothy, a retired nurse and a poet, is on the board of the South Fork Conservancy. They say the creek and its trails restore them.

Along a section of the trail known as the “confluence,” Dorothy says she is in a cathedral of trees where dappled light filters through the green above, forming a work of art.

Some homeless people live under the I-85 bridges along the trail. They set up camps with goods largely accumulated from other people’s castoffs—the salvageable among the debris that people from all walks of life regularly discard along, or even in, the creek.

On a recent morning, the Sussmans gathered a trash barrel full of cans, discarded paper wrappers, and even old underwear. An obviously homeless man they met on the path thanked them for their efforts.

“This points to the need not only to maintain the trails but to the very real need to help people who have no place to live,” Dorothy said. “I am very well aware that I can be on the trails and then go back to the comfort of my home. It’s a conundrum.”

Richard and Dorothy Sussman and their “granddogs,” Luna and Ruby, on a morning trail walk.

The environment is inextricably linked to social justice, said University of Georgia professor David Stooksbury, chair of the diocesan Commission on Environmental Stewardship. “In the last couple of years, we’re asking more questions involving issues of environmental justice. Many issues of degradation of the environment turn out to be justice issues. People with money are more likely to be able to adapt than poorer people. If climate change means summers are hotter, people with money just run the air conditioner longer,” he said. “Higher energy bills aren’t the issue for them. For people with fewer resources, it is an issue.”

Tropical diseases will become more widespread as the climate changes and people are more mobile than ever, he said. Then inequities in health care can be a factor. And concentration of agriculture and food processing means that contamination in one south Georgia peanut butter factory can cause illness and deaths all over the country. Those are facets of what’s happening to the environment as much as air pollution and plastics in the ocean.

Poor people are more likely to bear the brunt of all kinds of environmental abuse, he said. “The highest levels of pollution are in the poorest communities,” Stooksbury said. “A whole host of environmental issues have a social justice component to them.”

Stooksbury, a member of St. Gregory the Great parish in Athens, has a string of degrees in science and engineering, but he also relies on Scripture for his perspective.

“So much of the Old Testament is about the land,” he said. “It starts in Genesis 1 with the Creation story. We are surrounded by the abundance of nature. All we’re supposed to do is take care of it. Then sin enters the picture, and we lose the garden.”

In the New Testament, too, there are messages we should heed about the environment, he said. “The most quoted verse—at least at football games—is John 3:16,” he said. “‘For God so loved the world…’ It doesn’t say, ‘God so loved people.’ It says God loved the world.”

His commission on the environment has begun a collaboration with the diocesan Commission on Global Missions, he said. “We’re showing that the church is starting to realize that climate, that the environment in general, is a call for all of us, not just locally but globally.”

Faith and Hope || Environmental problems are religious crises because “at their core, they are crises of meaning,” the authors of Care for Creation wrote. Their book is an explanation of Franciscan spirituality. That theme was embraced by Pope Francis, who took his papal name from the earlier Francis. In an encyclical called “On Care for Our Common Home,” he expounded on the interconnectedness of God, humanity, and creation and explored how economic, political, religious, and social values affect the ways people look at and use the world’s resources.

The changing climate is costing some people their livelihood, he wrote, and some animals are unable to adapt. That is causing increased migration of people seeking to flee poverty. The loss of woodlands means a decreasing habitat for many species—plants and animals not only important to the cycle of life but that also have the potential of being sources for important advances in foods and medicines of the future. The spread of cities with inadequate transportation increases both visual and noise pollution.

Graffiti under the I-85 overpass at Piedmont Road in Atlanta. The trail crosses under the overpass as well.

Responsibility “for God’s earth means that human beings, endowed with intelligence, must respect the laws of nature and the delicate equilibria existing between the creatures of this world,” the pope wrote. “In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the word ‘creation’ has a broader meaning than ‘nature,’ for it has to do with God’s loving plan in which every creature has its own value and significance. Nature is usually seen as a system which can be studied, understood, and controlled, whereas creation can only be understood as a gift from the outstretched hand of the Father of all, and as a reality illuminated by the love which calls us together into universal communion.”

The impact of climate change affects “everything the church cares about and everything people of faith care about,” says Mosley of GIPL.

“We have done this to the earth, but we are not condemned because of it. We have another chance. Surely we can show compassion for what we’ve caused.”

— Sally Sears Belcher

To people who feel overwhelmed, she suggests looking at religious groups’ response to hunger. “I’ve been in churches since the 1960s,” she said, “and every church I’ve been a part of has had some kind of feeding ministry. That billions of people go hungry every day doesn’t keep us from packing meals and stocking the food pantry. We shouldn’t let the scale of the problem stop us from doing what we can.”

People of faith address hunger at different levels, she said: bringing in cans for the local food pantry, sorting food at the regional food bank, and advocating for policy change at local, state, and national levels. “We can apply that same approach to addressing environmental concerns.”

As a Christian, she said, she looks to Colossians 1:16-17: “For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him. And he is before all things, and in him all things hold together.”

“It says in him all things hold together,” she said. “All things. We have an image of Jesus with his arms outstretched sacrificially on the Cross—outstretched to reach all creatures, all beings, all things held together in Christ.”

Responsibility and Action || Research is going on that can show us new ways of raising and preparing our foods that will be more responsible, says Stooksbury of the University of Georgia.

Kindergartners are learning about butterflies and, through them, about the importance of every kind of creature.

Houses of worship are “going green,” or at least trying to do better, and good people of various faiths are lobbying for fairer, more responsible public policies.

Families are picnicking in a park on a site that used to be a toxic dump.

And religious groups of various faiths are taking a stand, such as this statement from the World Council of Churches: “The divine presence of the Spirit in creation binds us as human beings together with all created life. We are accountable before God in and to the community of life, an accountability which has been imaged in various ways: As servants, stewards and trustees, as tillers and keepers, as priests of creation, as nurturers, as co-creators. This requires attitudes of compassion and humility, respect and reverence.”

It’s true that humans, especially those in the Western world, have adopted practices that have damaged the garden God created, but that doesn’t have to be the end of the story. Redemption is possible.

“We have done this to the earth,” said Sally Sears Belcher, a television reporter and South Fork Conservancy founder, “but we are not condemned because of it. We have another chance. Surely we can have compassion for what we’ve caused.”

A Personal Note from Elizabeth Allan

Widow of Frank Allan, 8th Bishop of Atlanta

"I have spent some happy minutes pondering [the map of the south fork of Peachtree Creek], picking out what I know and need to know.

I grew up in Decatur, but had relatives all over Atlanta; so knew of access points to the Creek all over Fulton and Dekalb County. But my most wonderful memories come from the last 25 years of my mother's life when she lived in a little house on Desmond Drive off Clairmont—with a small branch of the South Fork right in the back of her yard! It was always flowing and clear, no problem in seeing the rocks and pebbles below or tiny critters flitting around. Our children loved visiting there—or staying a few days. My father had lived there for a few years before his death and had managed to hang an old-fashioned tire swing to a high limb on a huge tree. That swing lasted for years.

When Mother was still living, I started paying attention to other access points to the creek. And after her death, I kept exploring—Peavine Trail, Zonlite Park. Morningside Preserve, etc...Frank and I also lived near Emory—on Briarcliff, then Clairmont—and sometimes he would go with me to see if we could find a new trail mentioned in the neighborhood paper.

If you haven't discovered some of these spots, give them a try—a safe experience during the Pandemic. I now live further away from the South Fork, but this article is calling me to head that way again."