Enduring Truths

Calvin Johnson pulled his car up to the gasoline pump and waited for someone to come out of the service station to fill the tank. No one came.

He had never had to pump gas and was embarrassed to ask for help. He laughs now when he tells the story, but his experience at the self-service pump was a small example of the changes that occurred during the time he lost—sixteen years in prison for a rape and burglary DNA proved he didn’t commit.

Ellie Harold was molested by a priest at her Catholic school in metro Atlanta when she was ten years old. She felt helpless and powerless against the hierarchy of an international institution.

Sam Mihara was nine when his family was removed from their three-story Victorian house in San Francisco and packed onto a train to be taken to the Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming during World War II. His father went blind from untreated glaucoma, and his grandfather died of colon cancer during the family’s time there.

And Charles Person was put into solitary confinement in 1961 for the offense of singing too loudly. He had been arrested and jailed for participating in a sit-in at a segregated restaurant in Atlanta’s federal building, where young Black men like him were required to go to register for the draft but weren’t allowed to buy so much as a cold glass of iced tea.

Chances are that no one reading their stories had anything to do with the abuse they endured—or with the forced removal of Native Americans from Georgia in the Trail of Tears or with the enslavement and lynchings of Black Americans or with constructing the societal structures that prevented African Americans and women and gay Americans from exercising rights equal to those of straight white men. But all those wrongs were perpetrated in the United States while vast numbers of citizens either supported the perpetrators or looked the other way.

As demonstrators took to the streets in early June to protest the treatment of George Floyd and other people of color who died in police custody while begging for relief, Atlanta Bishop Robert C. Wright responded with a statement. “What looks like the behavior of a few bad actors is actually a system producing…the denial of dignity and safety to black and brown people, specifically black men,” he wrote.

As the bishop indicated, many of today’s inequities are rooted in the past. Many wrongs are still being committed, born out of old attitudes of racism, xenophobia, sexism, and homophobia. There is a sense that all of us need to have compassion for the people who felt—and still feel—the impact of collective wrongs and injuries.

“While we may not have specifically committed atrocities of the past such as land theft and slavery, the general white population has benefited from them,” said the Rev. Dr. Bradley S. Hauff, Episcopal Church Indigenous missioner. “Success came with a price somebody else paid. Many paid with their lives. Many paid with their lands.”

Imagine the country today, he said, “if theft of land from Indigenous tribes and theft of labor from slaves taken from Africa hadn’t happened. Those are horrible atrocities we need to own up to.”

William Faulkner’s oft-quoted line “The past is never dead. It’s not even past” rings true. After all, the Bible says the iniquities of the fathers will be visited upon future generations.

So what is our collective responsibility to the victims of past and present societal and institutional wrongs? The road to compassion starts with acknowledgment.

“If there is to be reconciliation, first there must be truth,” wrote Timothy B. Tyson, author of Blood Done Sign My Name, the true story of the 1970 gunning down of a Black veteran and its aftermath in Oxford, North Carolina. Tyson’s father, the pastor of the town’s all-white Methodist church, urged Oxford residents to come to terms with its bloody racial history. In the end the Tyson family was forced to move away.

Americans, Tyson wrote, “want to transcend our history without actually confronting it. We cannot address the place we find ourselves because we will not acknowledge the road that brought us here. … The work we face is to transcend our history and move toward higher ground. To find that higher ground, we must recognize, as Dr. King tried to teach us, that we are ‘caught up in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.’”

Saying “I’m Sorry”—Or Not || Rep. Andy Welch, R-McDonough, chairman of a legislative subcommittee, was presiding over a hearing to determine whether Jakeith Robinson, an imprisoned man who had repeatedly been denied access to the appeals process, would receive monetary compensation. Welch looked Robinson in the eye and told him he didn’t

know whether he could be given any money, but that he, Welch, wanted to apologize to Robinson on behalf of the committee and the justice system for what he had been through. Robinson stood up and, with tears in his eyes, thanked Welch and the committee. Welch’s expression of regret, Robinson said, was the first time anybody had apologized to him.

Welch said in a recent interview that he was surprised and saddened to learn no one else had expressed regret to Robinson about the failure of the system. “For him to forgive those who wronged him, someone has to acknowledge the wrong,” Welch said.

Calvin Johnson—proven innocent through DNA testing and released from prison in 1999—has been an employee of MARTA for over twenty years.

A committed Christian, Welch said: “I think compassion for those who have suffered injustice is part of the ministry of Jesus when he walked here on earth. I think it’s part of the ministry we are called to do.”

As someone who was badly wronged by being imprisoned on a false conviction, Calvin Johnson was bitter and angry for a while. His emotions, he said recently, were “like a rubber band,” stretching until he thought he might snap. Through prayer and Bible study, he calmed down. Even some relatives urged him to say he committed the crime so that he could participate in a program for sex offenders that would increase his likelihood of parole. He refused to lie about his guilt.

Real hope came when James C. Bonner, a lawyer who was part of the Prisoner Legal Counseling Project operating out of the University of Georgia, listened to Johnson and agreed to read the transcript of his trial. Bonner “took me seriously,” Johnson said.

First through Bonner and later through New York attorney Barry Scheck, Johnson was able to have DNA tests performed on old evidence that proved his innocence. In June 1999, at age forty-one, he became the first Georgia prisoner freed by DNA.

Johnson, now a twenty-year veteran employee of MARTA, received $500,000 in restitution for his sixteen years in prison, the equivalent of $31,250 a year. Money couldn’t buy back the time he lost with family and friends, but, he said recently, he was heartened not just by the lawyers’ work but by their attitude toward him. “It meant lots after years of being incarcerated to have somebody believe in me.”

A moment of irony happened a few years after his release, when he was summoned for jury duty in the same Clayton County court where he had been sentenced. He met the judge from his trial in the hallway. People who knew the circumstances of the two men stood silently and watched to see what would happen. Unable to avoid Johnson, the judge said, “Good to know you’re doing fine,” and walked on. It was the only recognition anyone associated with the case ever showed him, Johnson said.

All too often, people actually involved in wrongful convictions are hesitant to admit that mistakes were made, said Clare Gilbert, executive director of the Georgia Innocence Project. “They may not want to recognize the wrongdoing. They refuse to say, ‘I’m sorry.’ It makes it a lot easier on the person who has been wronged to have someone admit and acknowledge and recognize and apologize. When that isn’t present, it can be really hard for someone to move on and heal.”

Stuck at Ten || For almost forty years, Ellie Harold felt incapable of moving on. In 2002, after seeing a 60 Minutes report of sexual abuse by priests, Harold decided to go public through The Atlanta Journal-Constitution with her own story. Soon she was getting calls and letters from other girls who, like her, had been pupils at the same school in the 1960s and who had been molested by the same priest.

“In the absence of acknowledgment, the abuse continues,” she said. “In my case, it seemed a part of me remained as a wounded child in spite of having been in therapy on and off for thirty years. I saw this in my former classmates as well. Having found no one to help us at the time we were being abused, it was as if we were still kids, looking around for an adult in the room to be responsible.”

A breakthrough for Harold came when Father Dennis Steik, provincial of the Marist order that had run the school, called with a simple message: “I believe you.”

The two collaborated on a “Ceremony of Hope and Healing,” during which Steik gave each of eight women participants a check for $25,000 and a tiny gold cross decorated with a red rose, a symbol, he said, of sacrifice, pain, and resurrection. He also presented each woman with a ceramic statue of Jesus with children at his knee.

“They’re little things,” Steik said, “but a lot of love comes with them.”

Harold said her healing began with Steik’s statement of belief and felt complete after the ceremony.

A minister in the Unity Church, Harold had begun to teach herself to paint. She spent part of her settlement money on quality art supplies and travel to locations to paint. “Once freed from my attachment to the past,” she said, “I believe I was shown this art path, and, following it now, I feel I’ve found my true purpose.”

Australian author Craig Silvey writes about the importance of a genuine apology such as the one Steik gave the women.

“Sorry is a lot of things,” Silvey says. “It’s a hole refilled. A debt repaid. … Sorry doesn’t take things back, but it pushes things forward. It bridges the gap. Sorry is a sacrament. It’s an offering. A gift.”

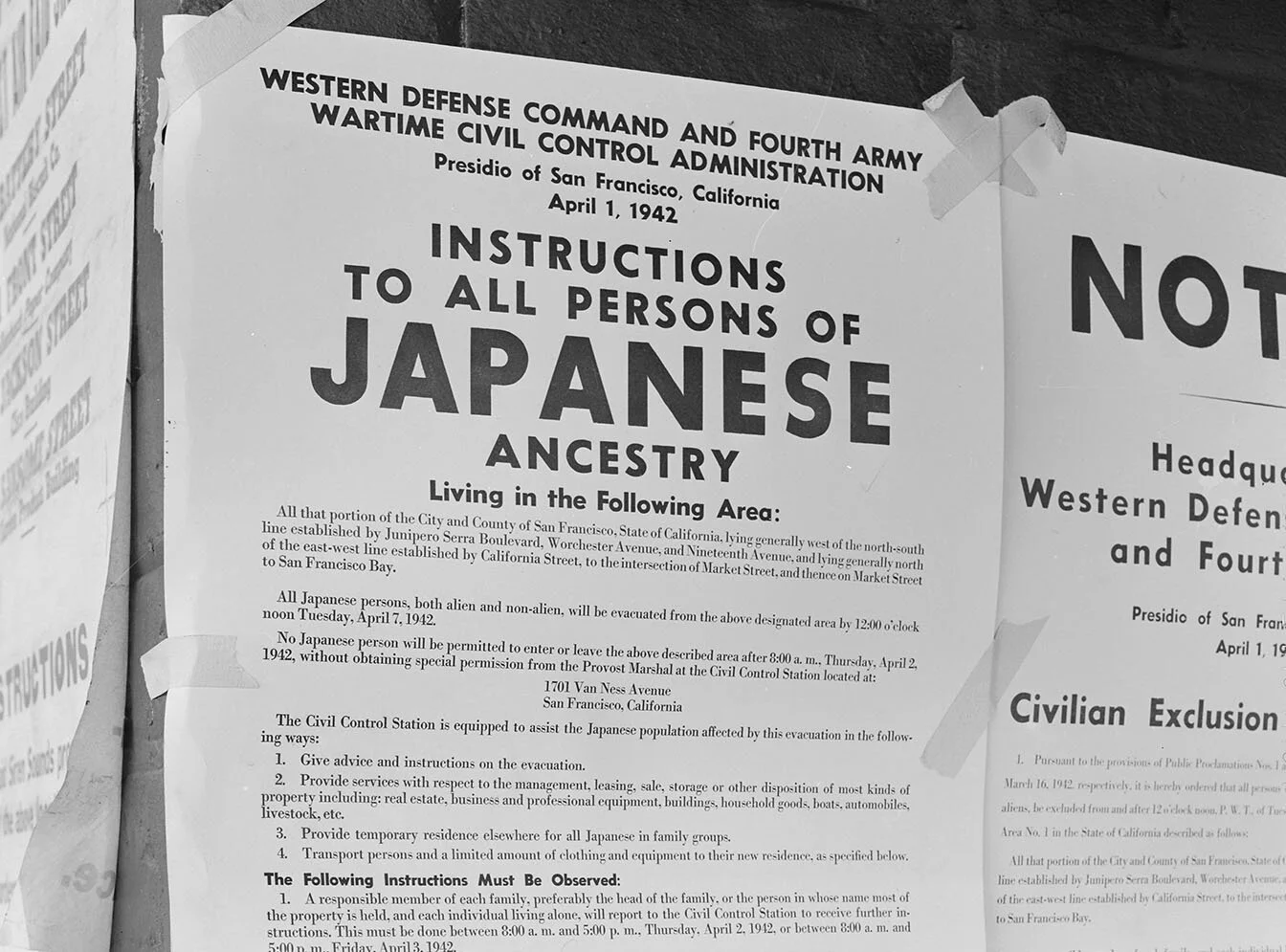

It is Written || The public apology issued to Japanese Americans by President Ronald Reagan in 1988 for their internment during World War II “is a record that those of us who went through the camps can cite,” said Sam Mihara, a retired executive with Boeing. “A written apology is a clear testimonial that the person making the apology really believed what happened was a mistake. Taking responsibility for what should not have been done is an important milestone.”

Mihara, his mother, father, and older brother spent three years, from 1942 until 1945, living in a single room without running water and with a single lightbulb. Three hundred people shared ten toilets, with no partitions between them.

Mihara’s parents, both born in Japan, had not been able to become U.S. citizens because of a prohibition on naturalization for nonwhite immigrants, who were classified as “aliens ineligible for citizenship.” He sees the internment, sparked by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, as resulting from the same vein of discrimination.

More than one hundred thousand American residents of Japanese descent sent to internment camps during World War II.

Just as acts of abuse are often part of a continuum of negatives—such as slavery to lynching to segregation to disproportionate incarceration of Black men—so acknowledgment and apology should be steps in an effort to recognize past sins, make amends as much as possible, and prevent future abuses.

William Shakespeare wrote in The Tempest, “What’s past is prologue.” The rest of the thought is quoted less frequently: “but the future is still to be written.”

Sitting In and Singing Out || One way to write the future is to pass stories of one’s experiences on to the next generation, said Charles Person. “A lot of stories have not been told,” he said.

Person, a member of the Church of the Incarnation in Southwest Atlanta, was a student at Morehouse College in 1961 when he took part in the Atlanta Student Movement. He was one of twenty-six students arrested on trespassing charges for refusing to leave the segregated Sprayberry’s cafeteria in the federal building.

Most of the students refused the $100 bail and opted to stay in jail. Person was there for sixteen days, ten in solitary confinement. Students in jail communicated information by singing and changing the lyrics of their songs. When jailers didn’t like the volume of Person’s voice, they put him into a cell alone, with only a bare mattress.

Map of the Freedom Rides featured in newspapers at the time.

Credit: AP

Person, just eighteen years old, also took part in Freedom Rides, boarding a bus from Washington, D.C., and traveling into Alabama to protest the lack of enforcement of court orders to desegregate. He was beaten so hard he had to have surgery for a head injury. Later, he was subpoenaed to testify against Klansmen in Montgomery. No one was convicted.

Person said he has received no great apologies or acknowledgments about the past but has found real admiration in students whose classes he has addressed. A retired marine and Vietnam veteran, he participated in Somewhere Listening for My Name, a book of stories of activists by Angela Duerson Tuck and Charles Williams Jones Jr. And he enjoys speaking at schools.

Charles Person, a Vietnam War veteran and member of the Church of the Incarnation, was part of the student movement during the civil rights movement and faced both arrest and attack for his efforts.

“Young people want to see change,” Person said. “That’s where the hope is. We don’t know what bus they’ll get on, but there will come a time when they will have to make a decision.”

We Only Have Today || Calvin Johnson and Sam Mihara are also relying on education about the past to help change the future. Johnson collaborated with a writer to tell his story in Exit to Freedom. He also works with the Innocence Project, which is focused not only on helping innocent people win release and helping them to adjust when they are out but also works to reform the criminal justice system to prevent false convictions. “Younger people are our future,” Johnson said. “They’re the future lawyers, judges, and politicians.”

Mihara, who has spoken to more than sixty thousand people, says it is important for people to look beyond the internment camps to the reasons they existed: racial hatred, mass hysteria, and leaders willing to ignore the U.S. Constitution. He encourages people to examine modern-day events in light of those conditions.

Harold is reaching out through her art. “I practice a kind of backdoor activism,” she said. “I paint. And then I put my paintings to work in service to bringing hope and healing to the troubles in our world.”

We may admire people who turn their experiences of abuse, discrimination, and persecution into positive attempts to help other victims and to prevent future injustices, but we shouldn’t leave it to those who have suffered to stand alone.

Writing the future should be the work of many scribes, and it should not wait.

Said Mother Teresa: “Yesterday is gone. Tomorrow has not yet come. We have only today. Let us begin.”

Looking west on “F” street, the main thoroughfare of Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, with it’s namesake “Heart Mountain” looming in the background.